Please join me for part two of an in-depth look at the seminal book that started it all: The Montessori Method. The first post in this series looked at the world and beliefs of Dr. Montessori in order to take a more holistic approach to how a book like The Montessori Method came to be written. Today’s post will cover chapters 2-5, giving an overview of the themes these important chapters contain.

History of Methods

In chapter 2, we are introduced to the concept of scientific pedagogy – basically, the art of being a teacher who observes and experiments in order to arrive at optimum methods of education. Dr. Montessori saw herself as carrying on the great work of two predecessors: Itard and Seguin. Jean Marc Gaspard Itard became known to the early 19th century world as the physician who worked with the so-called Wild Boy of Aveyron – an abandoned youth who had lived for years in the wilderness. Itard developed methods of sensory training and individualized education in the process of attempting to civilize his patient.

In turn, his methods were taken up by Dr. Eduard Seguin who wrote extensively about

the development of self-teaching materials for children considered to be mentally deficient. Maria Montessori highly regarded the discoveries of these men of science, and put their theories to work when the opportunity arose for her to begin working amongst children classed as ‘defective’. Eventually, she concluded that, if applied to ‘normal’ children, the findings of scientific pedagogy would produce amazing results.

Inaugural Address

Chapter 3 is, perhaps, the most emotionally moving section in The Montessori Method. We have the opportunity to read Maria Montessori’s complete inaugural address on the opening of one of her Children’s Houses. Her depiction of the intense destitution and despair encountered in the slums of Italy is haunting, and sets the stage for her stirring introduction to the purpose and power of the renovated, communal homes being erected to offer poor families the chance of a better life. The responsibility for the upkeep and harmony of these revolutionary homes rested on the shoulders of the residents, and one of the key benefits they offered was the presence of interior Children’s Houses for the care of children too young to attend school.

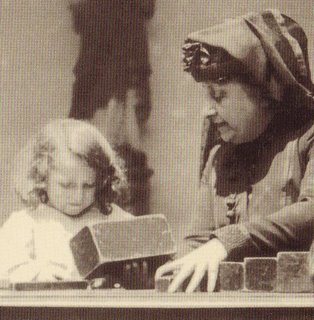

The industrial revolution and economic pressures made it imperative for poor Italian women to work outside the home, often leaving their babies and young children locked in empty, dangerous dwellings. By living in one of the new communal homes, each mother had the tremendous relief of knowing her child would be beautifully cared for by the Children’s House directress and attendant physician while she was away at work. Little by little, this arrangement led to Montessori’s development of her methods of teaching language and math skills, in addition to all of the modes of helping little children to become self-reliant and considerate community members. These Children’s Houses are the models upon which today’s Montessori schools are based. (See picture: Dr. Montessori in Rome giving a lesson in the Brown Stair. The year is 1911).

The industrial revolution and economic pressures made it imperative for poor Italian women to work outside the home, often leaving their babies and young children locked in empty, dangerous dwellings. By living in one of the new communal homes, each mother had the tremendous relief of knowing her child would be beautifully cared for by the Children’s House directress and attendant physician while she was away at work. Little by little, this arrangement led to Montessori’s development of her methods of teaching language and math skills, in addition to all of the modes of helping little children to become self-reliant and considerate community members. These Children’s Houses are the models upon which today’s Montessori schools are based. (See picture: Dr. Montessori in Rome giving a lesson in the Brown Stair. The year is 1911).

Discipline

Chapters 4 and 5 further explain Montessori’s devotion to a methodical study of individual children. Careful records were kept for each child, ensuring that the directress, physician and the parents would have ample documentation of the child’s health, growth and progress. Of particular interest is Montessori’s description of the ideal Montessori directress:

From her scientific preparation, the teacher must bring not only the capacity, but the desire to observe natural phenomena. In our system, she must become a passive, much more than an active, influence, and her passivity shall be composed of anxious scientific curiosity, and of absolute respect for the phenomenon she wishes to observe. The teacher must understand and feel her position of observer.

This was a revolutionary concept. Here, the child, not the teacher, becomes the focus of the learning environment. This is the untraditional arrangement you will find in today’s Montessori classrooms and homes, and it all began with Montessori’s love of both science and the phenomenal potential of the individual child’s mind.

Montessori advocates the abolishment of both prizes and shaming punishments. The Montessori Method gives memorable examples of the dangers of crushing a child’s first expressions of self, as well as the foolishness of making trinkets the reward for learning, rather than knowledge being its own reward.

Montessori’s great goal of the peaceful child and the peaceful community shines through in these chapters. Her depictions of the early struggles, failures and triumphs of the Children’s Houses will be highly instructive for anyone considering Montessori education.

The final post in this series will cover the remaining chapters of the book which put Montessori methodology into action. I’d like to end here with a quote from these early chapters in which the respect for the individual child is emphasized as crucial to the method:

It is remarkable how clearly individual differences show themselves, if we proceed in this way; the child, conscious and free, reveals himself.