Learning begins with naming. Young children have been carefully observing their surroundings since infancy; the key to unlocking all that knowledge is to give them the names of everything they see. Think about the very first words a baby responds to: his or her own name, and “mama” and “dada”. Picture a toddler, frantically pointing out the car window, wanting to know the name of everything they see. Naming is powerful.

That’s why we emphasize nomenclature cards so heavily in the early years. Technically, the word “nomenclature” means ” a set or system of names or terms used by an individual or community, especially those used in a particular science or art.” In Montessori terms, nomenclature simply refers to the naming of different kinds of nouns, or their parts, or their types.

That’s why we emphasize nomenclature cards so heavily in the early years. Technically, the word “nomenclature” means ” a set or system of names or terms used by an individual or community, especially those used in a particular science or art.” In Montessori terms, nomenclature simply refers to the naming of different kinds of nouns, or their parts, or their types.

Here’s Where Nomenclature Cards Come In…

The very first nomenclature cards are simply pictures, labels, and pictures with labels. All that matters is the object and its name. Parts are isolated (usually by color) and the pictures with labels provide the all-important control of error. Even a child who can’t read yet can match up letters and figure out which label goes under which picture.

Young children, especially those in the 3-6 age bracket, thrill to learn the parts of a leaf, mammal, or even the earth itself. However, at a certain age, naming is no longer enough. The child wants to know more. This is why we add the next phase to the nomenclature cards: definitions. The definitions give the child that extra information that they’re longing for. Now, the names are just the beginning. They are the springboard to learn how, what, when, where, and why.

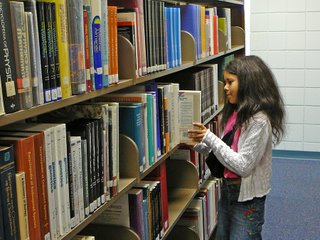

But then the child enters another stage. Now, the definitions (already handily written out) are limiting. The child has questions that the definitions cannot answer. They want more information; they are ready for research. There’s a sense of power that comes with being able to find out information on your own. Elementary-age children, with their powerful curiosity about the world around them, are ready to start learning on their own.

How Do You Introduce Research?

The very first kind of research should be simple, with specific questions that can be answered by the child. These Research Guides are the perfect example; using guided questions gives the child a framework with which to pursue additional information.

A younger child who is interested in researching something will probably need help, especially if they are just beginning to read and write. An older child will need an introduction to the world of reference materials, but after that they will be able to complete research on their own.

It’s very important that children understand what to do with the information that they find. I always emphasize that answers to questions be written in complete sentences; it’s a good habit to encourage. They must also learn that answers must be restated in their own words, and that they might need to combine information from more than one source in order to get the information they need.

Advanced Research Projects

After a child has mastered the art of answering simple research questions, they are ready to tackle a research project. When conducting this type of research, a child will definitely want to use more than one source, and take notes on index cards before compiling and rewriting the information. This type of project may culminate in some sort of presentation given to a class or even the parents. See this post, Ten Steps to Outstanding Student Presentations for more info.

When choosing sources for more advanced research, children will naturally gravitate towards books, including reference books like atlases and encyclopedias. At this point, they may need some specific instruction on using these types of books. You may want to point out things like the table of contents, indexes, and other helpful points of interest.

When choosing sources for more advanced research, children will naturally gravitate towards books, including reference books like atlases and encyclopedias. At this point, they may need some specific instruction on using these types of books. You may want to point out things like the table of contents, indexes, and other helpful points of interest.

Today’s child is likely to use the internet for quite a bit of research. There’s no doubt it’s a phenomenal way to find pictures, videos, articles, and other helpful information. Due to the nature of much online content, I always recommend that children use a child-safe search engine like Yahoo Kids rather than Google or Yahoo, and that they only work in supervised areas where adults are present.

The Pitfalls of Research

On one hand, research is the hallmark, maybe even the cornerstone, of a Montessori 6-12 education. On the other hand, it is sometimes introduced too early and done incorrectly. I have walked into Montessori classrooms where first graders were copying sentences word-for-word out of the encyclopedia. If you ask them what they’re working on, they look up, smile, and say “Research”. This is not research, it is plagiarism. Unfortunately, it’s the unavoidable outcome of encouraging research too early, before the child has the necessary skills to do it correctly.

Why does this happen? Well, it makes it seem that the children can do higher level work than they really can. It makes their work look impressive. It gives an observer the feeling that the child is very advanced. And, it makes the teacher feel that they are practicing “real” Montessori, where children learn from reference books rather than teacher-made materials.

The sad byproduct is that children who start research too early are usually missing out on crucial math, language, and cultural materials that would lay a firm foundation for future learning. They’ve jumped ahead too soon, and important concepts are neglected in favor of “research”. They are also being led to believe that research is simply using someone else’s ideas and calling them your own.

Doing It Right

Done correctly, research is a fantastic way for children to learn. Rather than being confined to the information we set before them, research is a chance for the child to direct their own path of learning. The end result is a child who is confident that they can find information if and when they need it, without needing to rely on others. Basic research skills will aid a child throughout an entire lifetime of learning.